5 More Myths about Editing

As a follow-up to a blog post I wrote that discussed six myths about editing, I’m bringing you five more myths that I’ve heard.

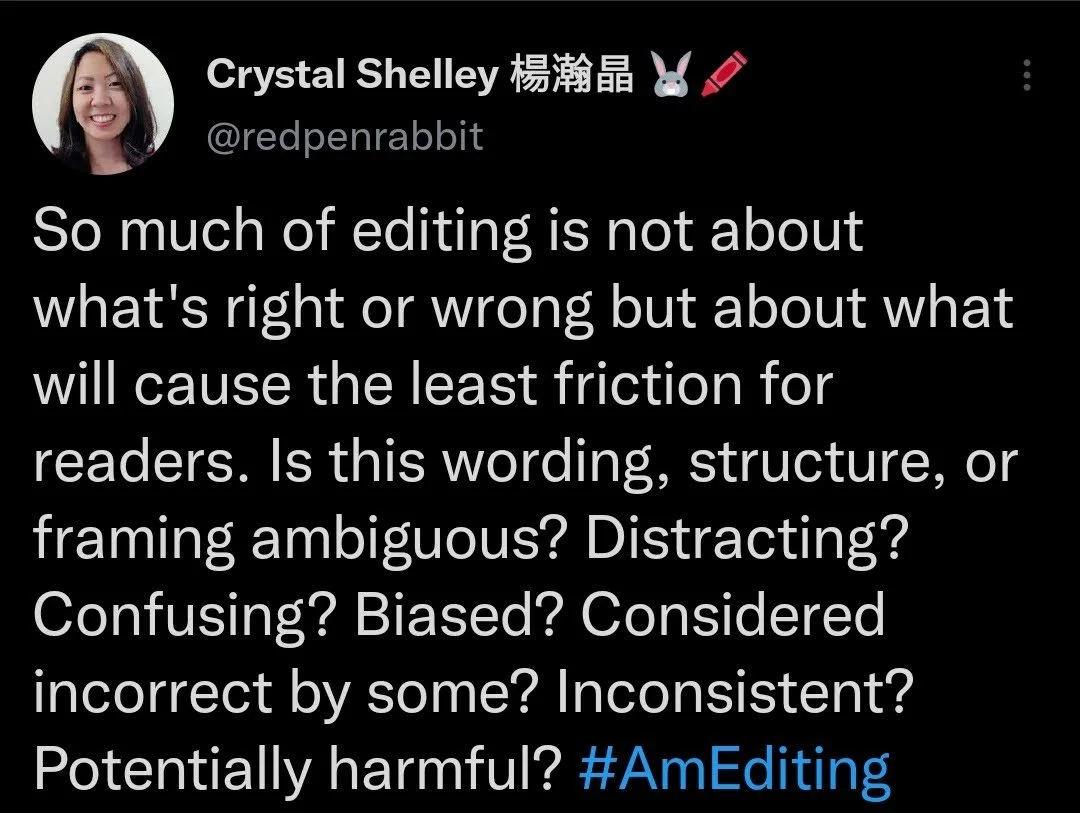

Myth #1: Editors follow a set of rules that tells them what’s right or wrong.

When it comes to writing, especially grammar and punctuation, there’s often this notion that something is right or wrong, that all answers are clear cut. Many of us are taught in school that English is bound by a set of rules, and it’s always incorrect to break those so-called rules, regardless of the context. When we think about writing in terms of absolutes, we force ourselves to follow prescriptive rules and then expect others to follow those too.

That’s why if you ask editors a question about whether a word, punctuation, or style is correct, don’t be surprised if they tell you “it depends” or ask a ton of follow-up questions to better understand the context. Trained editors understand that there are few yes/no answers and a whole lot of maybes, and flexibility is often needed.

So what do I mean by writing “rules”? Here are a few you might have heard before:

“Separating two independent clauses with only a comma and no conjunction (a comma splice) is incorrect.” Comma splices can be used effectively in certain situations, so banning them from all writing is a stretch.

“Always use double quotation marks for dialogue.” What style is the story written in? Double quotation marks are the convention for punctuating dialogue in US English, but not in British English. And even then, this is a style recommendation and not a rule. Readers might be initially thrown off if the dialogue is denoted in a different way, but that’s not to say that everyone must always follow the convention.

“Never tell the reader something that can be shown.” Yes, showing action or emotion can be more effective than telling the reader what’s being done or felt, but sometimes telling works better.

Yes, editors usually follow a style guide and a preferred dictionary when editing. But skilled editors know how to assess the context and the author’s style so that they can decide whether to follow the established conventions or break from them.

Myth #2: Writers have to accept every change an editor makes.

The word stet is Latin for “let it stand,” and it’s a powerful word that every writer (and editor) has at their disposal. When an editor makes a change to a manuscript that a writer doesn’t agree with, then the writer can write stet next to the revision to indicate that they want to ignore that change and retain the original wording. Maybe the editor misinterpreted the meaning of a sentence and accidentally changed it with their edit. Or maybe the change they made didn’t sound like the author’s voice. Or maybe they introduced an error into the text. Whatever the reason for rejecting a change, the writer has the final say in what they accept or reject for their own writing.

An editor working in Word or Google Docs will typically track all of their changes so that the writer can see what was done. This gives the writer the ability to decide what to do with those changes. Edits are usually recommendations. Some edits are pretty objective, such as when an editor fixes a typo or inserts a missing punctuation mark, but many of them are subjective. Editors don’t expect writers to accept all changes. It may be wise to consider why an edit was made, but if a writer doesn’t like an edit, they’re not obligated to proceed with it.

Myth #3: Good editors shouldn’t need software to help them.

One of the myths I talked about last time was the notion that professional editing isn’t needed because of technology like Word’s Editor tool (formerly spell check and grammar check) or plugins like Grammarly. I firmly believe that these tools are not a replacement for trained editors, at least not in their current iterations.

That said, I’ve seen editors judge other editors for using software and plugins, and I’ll be the first to say that I use them. With every edit, I run Word’s Editor tool to check for any misspelled words I may have overlooked, and I run a program called PerfectIt that helps me with consistency and style. I don’t rely on these tools to do my job, but they’re useful for quality control when I’m wrapping up a project.

Editors don’t need to use software, by any means. But the implication that an editor who does use tools is inferior to one who doesn’t rubs me the wrong way. I recognize that I’m not perfect and I may miss some things, so having tools that back me up in my editing means that I’m potentially catching more in the manuscript than I would’ve on my own. At the end of the day, the goal is to send my client the best version of the manuscript I can, so you can bet I’m going to take advantage of whatever programs I can to make that happen.

Myth #4: The most expensive editor is the best one, and the least expensive is the worst.

I’ve talked about the costs of professional editing before, but one myth I’ve heard related to editing costs is that what an editor charges correlates with the quality of their work. The idea of “you get what you pay for” plays into this heavily, and while this adage might often be true when it comes to the quality of an edit, it may not always be the case.

Many editors set their own rates, so those rates could be based on any number of factors: how much they need to make in order to pay the bills, how much experience they have, how busy they are, or anything else. However editors decide on their rates, that’s their business (literally). Just because Editor A charges very high rates, it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re better at editing than Editor B, who charges lower rates. And that doesn’t mean Editor B is better at editing than Editor C, who charges even lower rates. There’s no hierarchy of editing quality based on rates.

Will a writer get a quality copy edit for their 80,000-word manuscript if they pay $100? I don’t know. I can say that that’s a fraction of what I charge, but I can’t know what an editor who charges that much will do. Maybe the editor will just run the writing through some editing software and call that good. Or maybe that editor is looking for experience, or they really need to make ends meet and are severely discounting their rates to book projects.

No matter what editors charge, writers can find someone at every price point. It’s just a matter of what you’ll get at that price point, and that’s between the editor and the client.

Myth #5: Editors have all style guides, dictionary entries, and conventions memorized.

Contrary to what some people might think, editors don’t know the definition or spelling of every word, and they don’t know every guideline from The Chicago Manual of Style or AP Stylebook.

There’s a reason why editors have reference books they frequently consult, as well as internet search histories that would raise many an eyebrow. No one has every piece of information memorized, and that goes for editors too. Rather than thinking themselves infallible, effective editors know when and where to look things up.

I used to be extremely confident in my knowledge of grammar and spelling, and it wasn’t until I became an editor that I started to second-guess myself. That’s not to say I’m not skilled in those areas, but I now recognize that just because I’m confident doesn’t mean I’m infallible. I’d rather double-check a reference to be sure I’m enforcing a style consistently or spelling a word correctly than to risk being wrong about it. Clients don’t pay me to guess. They pay me to use my knowledge and my training to their full extent, which means knowing when I don’t know something.

Final thoughts

That’s five more editing myths down, and many more to go. What are some of the most pervasive editing myths you’ve heard?